If I asked you to separate helloworld into meaningful words, you would immediately

jump to hello and world before your mind could even consider that the first word

might be he or hell.

You’ve just created a token boundary using only a pre-existing knowledge of the language. In other words, the token boundary wasn’t encoded in the source material — you used outside information to infer one.

This isn’t how parsers work.

Computer languages are designed to be tokenized unambiguously. This is achieved by encoding token boundaries into the source material.

This comes at a price.

Knowing token boundaries

Whitespace is the most apparent token boundary. The space between class and Configuration

allows the lexer to separate them into two distinct tokens.

| |

The less obvious token boundary is this:

| |

There are no spaces here, and yet, we know exactly how to tokenize this text.

You are probably a human looking at this example in a human way and seeing operators and variables. I think you would appreciate my point more if the source looked like this1:

[459.99, 408.88, 457.3, 384.67, 458.645]

The token boundaries aren’t so obvious now, are they?. How do you decide where to draw the lines?

We implicitly know that = does not belong in the same set as c and a.2

Therefore, c and = cannot be a part of the same token. Therefore, there must

be a token boundary between c and =.

This tells us that token boundaries are encoded in the change of character sets of adjacent tokens.

The numbers example above can also be solved using this rule. We just need to know the set in which each number belongs.

The whitespace example is not an exception; it is a special case of this rule. Whitespace encodes two boundaries — the first boundary is encoded in the transition from keyword to whitespace, and the second in the transition from whitespace to identifier.

How many Shannons does it take

Scenario #1

To start with, we want to calculate the number

of Shannons3

the token boundary between c= occupies.

| |

Also, let

| |

Case 1

For this case, our token boundary is encoded in the change of character sets between the two tokens.

| |

In place of c, we could have 1 of 26 possible states. For this token

of length 1,

the Shannon entropy is:

| |

Likewise, in place of =, we could have 1 of 5 possible states. For a token

of this type, and length 1, Shannon entropy is:

| |

The total entropy of the source is:

| |

Case 2

For this case, let’s say that the token boundary is encoded separately, outside the source.

Since the boundary is not encoded in the change of character sets, each individual position can be filled with any character available to us (i.e. the union of operator and identifier sets)

The Shannon entropy for the source message can be calculated by:

| |

Entropy of the token boundary

| |

This means that this token boundary encodes ~3 Shannons worth of information. That’s roughly 30% of the total entropy of the message. Granted that the message itself is quite small, this is still a significant result.

Think about it this way - a certain character set is reserved for any given token. A boundary is detected where a character from the reserved set appears. Each character of the token carries information about the token boundary - specifically where the token boundary isn’t.

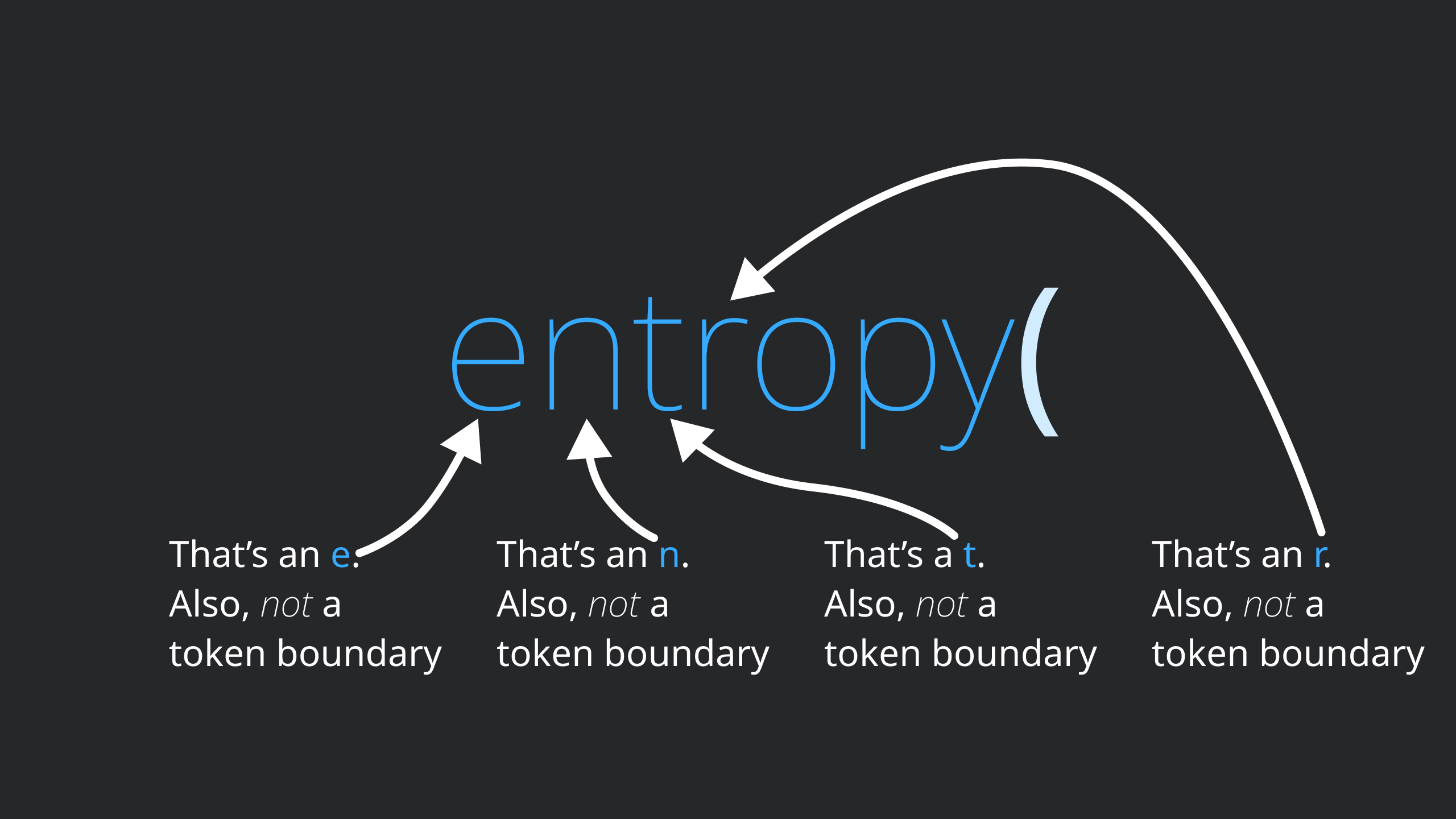

This is reinforced when you look at entropy() and notice that the entropy of a token

boundary is linearly related to the length of the token. This means that increasing the

length of the token by one character always increases the entropy by a fixed amount,

because each character of the token uses the same number of Shannons to encode the

token boundary.

Bits in the real world

The result we have seen above are quite generous in comparison with the real world. They don’t take into account the actual encoding of the file at all.

For a real-world metric, let’s say that our file is UTF-8 encoded, and for simplicity, let’s say that one character occupies exactly 8 bits.

That’s a total of 256 possible states, of which our identifier can use 63 (a-zA-Z0-9_).

This means that the remaining 193 states are reserved for the token boundary. In other words,

2 out of 8 bits of each character are reserved to encode the token boundary.